You turn on the porch light after sunset and notice something looks slightly off. The beam is softer, the glass looks faintly hazy, and the fixture does not feel as “clean” as it once did. It still works, so it is easy to ignore.

A few days later, after a warm afternoon followed by a cool night, that haze is still there. Maybe you even see a thin line of moisture inside the lens. Many homeowners assume rain must have leaked in, but in most cases, the real cause starts with air movement and temperature shifts.

Outdoor lighting is built to handle weather from the outside. What it does not fully prevent is humidity cycling inside the housing. As exterior lighting specialists often point out, condensation patterns typically begin long before visible corrosion appears.

The early stage rarely feels urgent. The fixture turns on. Nothing has failed. Yet subtle internal moisture cycles may already be affecting electrical contacts and structural materials in ways that are not immediately visible.

How Moisture Enters Sealed Outdoor Fixtures

You look at the fixture and see no cracks, no broken glass, no obvious gaps. So how is there water inside? That question usually comes up the first time condensation shows on the inner lens.

Most outdoor fixtures are weather-resistant, not airtight. Over time, small openings form in places you do not normally check:

-

Rubber gaskets that harden and lose flexibility

-

Wire entry points where sealant shrinks

-

Seams exposed to years of sun and temperature swings

During the day, warm air enters the fixture. At night, temperatures drop and that trapped air cools. Moisture inside the air turns into condensation on the inner surfaces. You notice the fog; the condensation cycle has likely been repeating for weeks.

Many homeowners assume water must have “leaked in” during a storm. In reality, the issue often starts with air movement and temperature changes, not heavy rain. That misunderstanding delays recognizing what is actually happening.

Early Warning Signs of Moisture Damage

One night the light flickers slightly, then returns to normal. You replace the bulb just in case, but the flicker comes back days later. That small annoyance is often one of the first signs of internal moisture.

Common early signals include:

-

A persistent fog inside the glass

-

Light that briefly dims or pulses

-

Metal parts that look dull instead of shiny

It is easy to blame the bulb. However, moisture inside the fixture starts affecting the socket and contact points long before a full failure happens. Oxidation builds slowly, increasing electrical resistance without making a dramatic change at first.

A common but mistaken belief is that a little condensation is harmless as long as the light still turns on. In practice, visible condensation usually means the moisture cycle has already been active for some time. What you see on the glass is often just the surface symptom.

Over time, those small changes add up. The fixture may still work, but it no longer operates under stable internal conditions.

Why Moisture Accelerates Electrical Failure

You may notice the light looks slightly dimmer on humid nights. Or it flickers when the temperature drops quickly after sunset. These patterns often point to moisture affecting electrical performance.

Moisture changes what happens inside the fixture in several ways:

-

It causes oxidation on metal contacts

-

It increases resistance at connection points

-

It can allow tiny unintended current paths between components

As resistance rises, heat builds at the contact points. Heat causes expansion, cooling causes contraction. That repeated movement weakens connections over time, even if nothing looks visibly damaged.

Moisture also affects how heat escapes the fixture. Bulbs generate warmth, and damp internal air can trap that heat longer than dry air. You may only notice that the light behaves inconsistently, but internally, materials are under added stress.

Electrical failure rarely happens overnight. It builds through repeated exposure and small internal changes that are easy to miss in daily use.

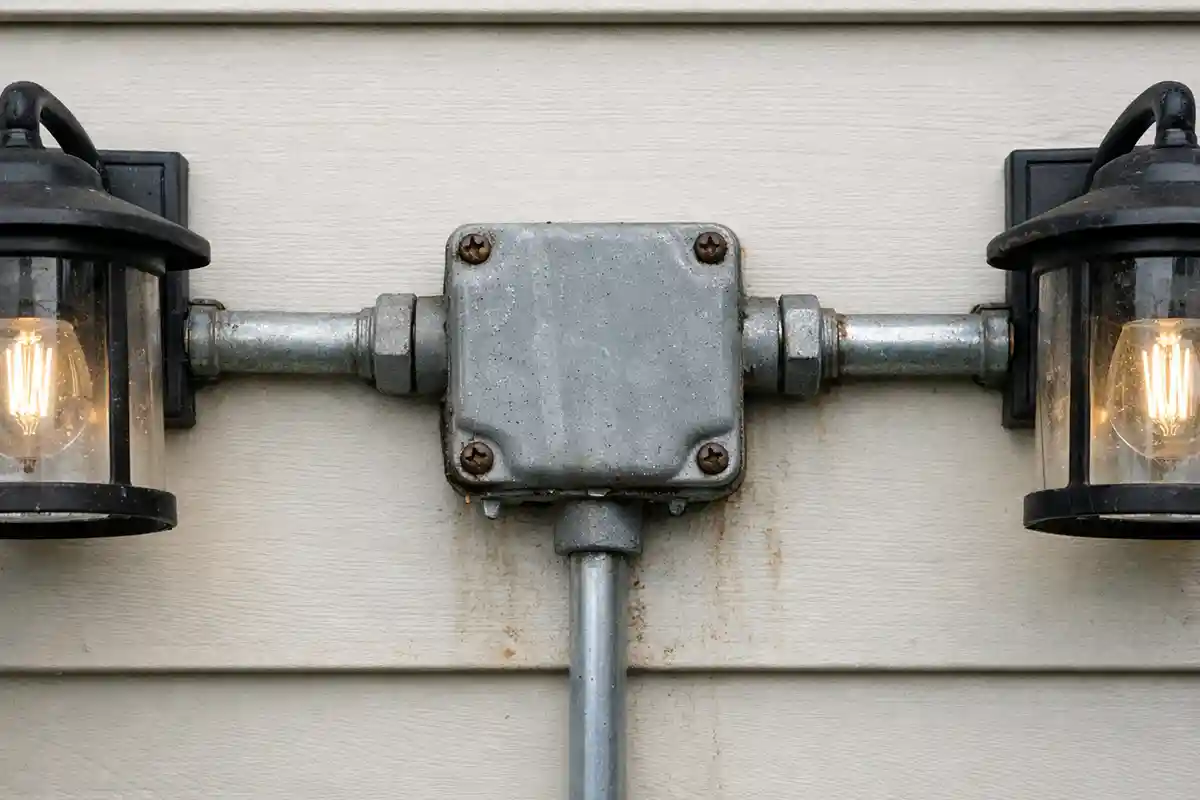

Structural Areas Most Vulnerable to Water Intrusion

If you remove an older fixture from the wall, you often see the real weak spots. They are usually small details rather than dramatic breaks.

The most moisture-sensitive areas include:

-

The gasket between the glass and housing

-

The point where wiring enters the fixture

-

The mounting plate pressed against the wall

-

Exposed screws and thin metal brackets

When gaskets stiffen, they stop sealing tightly. When sealant around wiring shrinks, humid air slips in. If water collects behind the mounting plate, the fixture can stay damp even after the weather clears.

Below is how everyday observations often differ from what is actually happening inside:

| What You Notice | What You Assume | What Is Actually Happening |

|---|---|---|

| Light still works but looks hazy | It is just dirt on the glass | Condensation is forming inside the housing |

| Occasional flicker | The bulb is loose | Oxidation is affecting electrical contact |

| Slight rust near screws | Normal outdoor wear | Ongoing moisture exposure is accelerating corrosion |

These signs rarely appear all at once. They build gradually and often seem unrelated at first. When viewed together, they reveal a clear pattern of moisture interacting with structural weak points.

Moisture damage in outdoor lighting is usually not caused by one heavy storm. It develops through repeated exposure, small material changes, and everyday temperature shifts that most people barely notice.

Climate Exposure and Compounding Moisture Cycles

You may notice the porch light behaves differently in July than it does in January. In humid summer air, condensation forms more often and lingers longer inside the fixture. In colder months, rapid temperature drops trigger sharper internal moisture events, even when rainfall is low.

Climate shapes how often condensation cycles repeat. Coastal air carries salt that accelerates corrosion once humidity enters the housing. Northern regions introduce freeze–thaw expansion that gradually widens small seal gaps. Dry climates with strong day–night swings can still create internal condensation purely from temperature contrast.

Over time, these overlapping cycles reinforce each other:

-

Warm air enters during daytime heating.

-

Cooling condenses trapped humidity.

-

Residual moisture remains on internal surfaces.

-

Repeated expansion weakens sealing materials.

What feels like random seasonal inconsistency is often a repeating environmental pattern acting on the same vulnerable points.

Internal Electrical Dynamics Under Repeated Moisture Exposure

You might notice the light pulses faintly on damp evenings but behaves normally during dry stretches. That inconsistency often reflects internal electrical stress rather than a failing bulb.

Moisture gradually alters the electrical environment:

-

Thin oxidation develops on metal contacts.

-

Electrical resistance increases subtly.

-

Heat concentrates at contact points.

-

Thermal expansion loosens connections.

As resistance rises, heat distribution shifts. As heat shifts, internal air pressure changes. Each change increases the likelihood of additional moisture cycling.

Over time, socket terminals, mounting hardware, and internal wiring insulation all experience layered stress. The failure process spreads rather than remaining isolated.

Why Does My Outdoor Light Flicker After Rain Even If No Water Is Visible?

You step outside after rainfall and the fixture looks dry. The glass is clear. The housing feels intact. Yet that evening, the light flickers briefly or dims without warning.

Surface dryness does not reflect internal humidity levels. External appearance often hides internal condensation activity.

Why does the light flicker only after humid weather but not during dry weeks? Because internal condensation alters electrical resistance without leaving visible water.

Why does replacing the bulb not solve the issue? Because oxidized socket contacts, not the bulb itself, often disrupt stable current flow.

Why does the flicker improve after several dry days? Because lower ambient humidity reduces internal moisture accumulation temporarily.

Why does the issue appear more often at night? Because rapid temperature drops increase internal condensation after sunset.

Why does the fixture seem stable for months and then act up suddenly? Because corrosion builds slowly until electrical resistance crosses a noticeable threshold.

These variations reflect moisture-driven electrical instability rather than isolated component failure.

Component-Level Interaction and Degradation Mapping

Different parts of the fixture respond differently to repeated humidity exposure. The progression is not uniform across materials.

| Component Area | Immediate Effect of Moisture | Progressive Structural Change | Visible or Behavioral Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socket Contacts | Surface oxidation begins | Rising resistance levels | Intermittent flicker or dimming |

| Gasket Seal | Reduced elasticity | Increased air exchange | Persistent internal fog |

| Mounting Bracket | Minor corrosion spots | Metal thinning | Slight fixture instability |

| Internal Wiring | Insulation absorbs humidity | Insulation brittleness | Irregular power delivery |

| Junction Interface | Humid air migration | Compounded corrosion | Multi-fixture inconsistency |

This comparison highlights why moisture damage rarely remains isolated to a single visible symptom.