You flip the switch, and the porch light comes on like always. Nothing looks unusual from the outside. What you do not see is the slow change happening inside the small metal connection points that carry electricity.

Outdoor lighting lives in shifting weather. Rain, humidity, heat, and cold move in and out of the fixture all year long. Over time, those changes quietly affect the metal connections that hold the system together.

Most failures do not start with a dramatic spark. They begin with subtle surface changes that build month after month until performance starts to drift.

What Corrosion Really Means in Electrical Connections

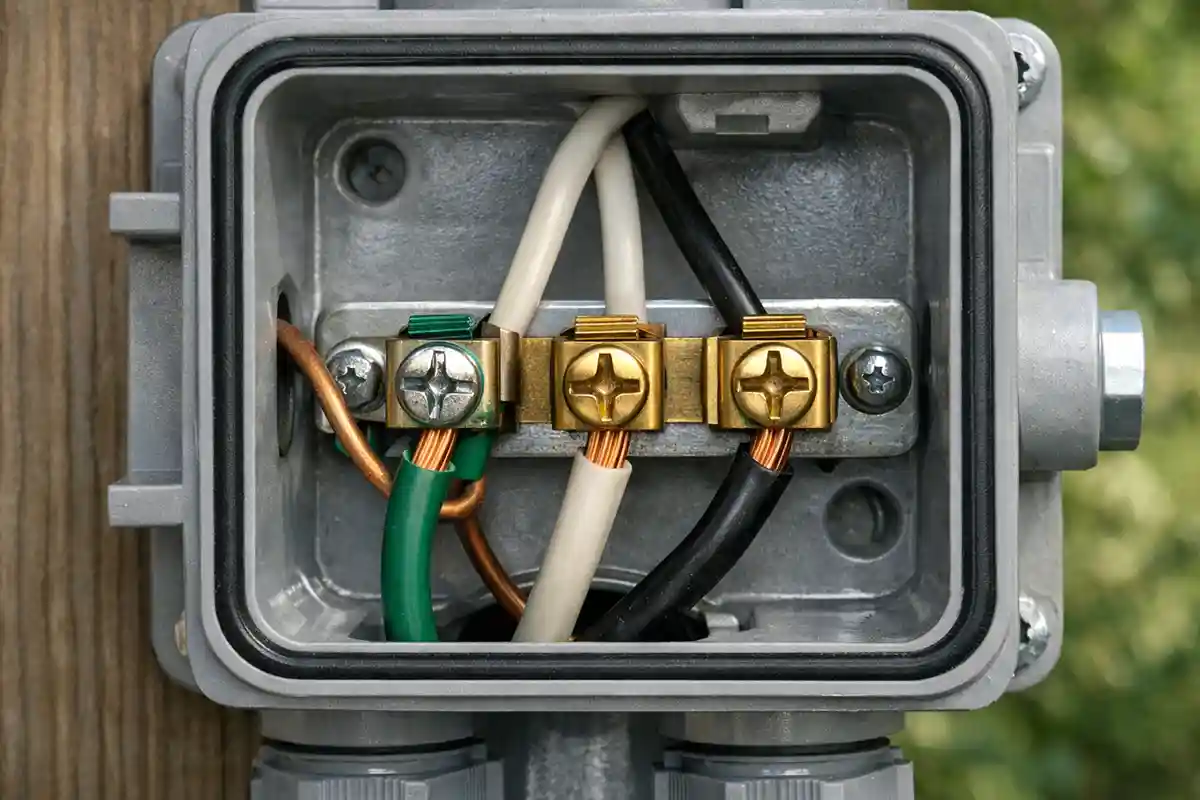

You remove a fixture cover and notice a dull green tint on the copper wire. The screw no longer looks shiny. That small visual change answers a common question: what is actually happening inside the connection?

Corrosion forms when metal reacts with oxygen and moisture. In outdoor light connections, this usually shows up as:

-

Green buildup on copper.

-

Reddish rust on steel screws.

-

Chalky white residue on aluminum parts.

At first, this looks cosmetic. In reality, even a thin layer of oxidation changes how electricity moves across the surface. The contact area becomes less direct, and current must pass through tiny remaining clean spots.

As resistance increases, a few things start to happen:

-

The connection warms slightly during operation.

-

The light may flicker in damp weather.

-

Voltage becomes less stable at the fixture.

These changes are easy to dismiss as bulb issues. In everyday use, you might only notice that the light seems dimmer on humid evenings. That subtle shift is often the first sign that corrosion has started to affect conductivity.

Why Outdoor Fixtures Are Especially Vulnerable

After a heavy rain, the fixture looks dry from the outside. Inside, however, moisture may still be present. Outdoor lights deal with more than direct rainfall.

Moisture enters in several ways:

-

Rain driven by wind.

-

Condensation forming overnight.

-

Irrigation spray hitting the housing.

-

Humid air trapped inside sealed fixtures.

When warm air inside a fixture cools at night, tiny droplets can form on metal parts. This repeated damp-dry cycle gives corrosion exactly what it needs: moisture and oxygen in contact with exposed metal.

Location also changes how quickly damage appears:

-

Coastal air carries salt.

-

Urban air contains acidic pollutants.

-

Areas with hard water leave mineral residue after evaporation.

Two identical fixtures can age very differently depending on where they are installed. In daily use, you may notice one side of the house develops problems faster than the other. That difference often traces back to environmental exposure rather than product quality.

Seasonal temperature swings add another layer. As materials expand and contract, screw terminals can loosen slightly. A barely loosened connection traps moisture more easily, which speeds up oxidation.

Early Warning Signs That Often Go Unnoticed

You might first notice a faint flicker during a rainy week. The bulb looks fine, and tightening it does not change anything. That moment often marks the beginning of visible symptoms.

Common early signs include:

-

Slight brightness fluctuations in damp conditions.

-

A faint buzzing sound from the fixture.

-

Discoloration on exposed screws.

-

Powdery or green residue near wire connectors.

These signals tend to be misread in everyday use:

-

A flicker is blamed on a cheap bulb.

-

Buzzing is assumed to be normal aging.

-

Green residue is seen as harmless discoloration.

-

Occasional dimming is ignored because the light still works.

| What You Notice | What You Assume | What Is Actually Happening |

|---|---|---|

| Light flickers after rain | The bulb is loose | Resistance is increasing at a corroded connection |

| Screw looks slightly rusty | It is only surface rust | Oxidation is reducing metal-to-metal contact |

| Fixture works most days | The wiring is fine | Early-stage corrosion is building under load |

These small misreadings delay attention. In daily life, as long as the light turns on most of the time, the issue feels minor. However, corrosion is cumulative, and each damp cycle adds another thin layer of oxidation.

A more comprehensive understanding of how moisture initiates these issues can be found in this detailed explanation: Moisture Damage in Outdoor Lighting Explained provides a clear breakdown of how water exposure evolves into structural electrical problems.

How Water Intrusion Accelerates Metal Breakdown

You open a fixture after a storm and see water droplets clinging to the inner housing. That visible moisture explains why corrosion can suddenly accelerate.

When water sits on metal, it creates a conductive path between different materials. If copper wire touches a brass screw inside a damp environment, an electrochemical reaction can begin. When different metals are involved, the reaction can become uneven and more aggressive.

Water intrusion typically follows a pattern:

-

Small gaps around mounting brackets.

-

Worn gaskets that no longer seal tightly.

-

Cracks in conduit entries.

-

Mineral deposits left behind after evaporation.

Each time water enters and then dries, it leaves behind residue. Those deposits trap more moisture during the next cycle. In daily use, this often shows up as problems that seem worse after storms and calmer during dry weeks.

The broader causes and warning thresholds of internal water exposure are explored in this resource: Water Inside Outdoor Light Fixtures: Why It Happens and When It Becomes a Problem outlines the environmental and structural triggers that lead to persistent moisture conditions.

The Long-Term Electrical Consequences

Months pass, and the light that once felt steady now behaves unpredictably. This is where small chemical changes begin to affect the entire circuit.

As corrosion progresses:

-

Resistance continues to rise.

-

Localized heating becomes more frequent.

-

Insulation may discolor.

-

Terminals can weaken physically.

In daily experience, you might notice more frequent bulb replacements or breakers that trip during bad weather. These are not random events. They are the visible outcomes of a slow shift inside the connection points.

Corrosion is not a one-time event. It builds in layers, shaped by environment, material pairing, and repeated exposure. What starts as a thin film on metal can gradually change how the entire lighting system behaves.

The Role of Oxidation in Progressive Signal Loss

A pathway that once carried electricity cleanly can slowly narrow without anyone noticing. At first, the light still turns on. The change happens at the microscopic level, where oxidation reduces the effective contact area between two metal surfaces.

As oxidation builds, current is forced through smaller conductive نقاط. This creates localized resistance, which leads to mild but repeated heating during operation. Over time, that heat slightly alters both the metal and the surrounding insulation.

In low-voltage systems, this often appears as uneven brightness between fixtures. In standard line-voltage wall lights, it may show up as occasional flicker during humid evenings. The bulb is frequently blamed, but the instability often begins at the connection itself.

The progression usually follows a pattern:

-

Surface oxidation forms.

-

Contact pressure becomes less effective.

-

Resistance increases under load.

-

Heat accelerates further oxidation.

None of these stages feel dramatic in isolation. Together, they gradually shift the system from stable to inconsistent.

Galvanic Interaction Between Mixed Metals

Inside many outdoor fixtures, different metals sit in direct contact. Copper conductors meet brass screws. Aluminum housings support steel brackets. When moisture bridges these materials, a small electrochemical reaction can begin.

One metal sacrifices itself faster than the other. The result is uneven deterioration that can surprise anyone inspecting the fixture. A screw may appear severely degraded while the surrounding conductor still looks intact.

This imbalance depends on:

-

The specific metals involved.

-

The presence of moisture.

-

Dissolved minerals or salt.

-

Repeated wet-dry cycles.

In coastal areas, salt increases conductivity within moisture films. In urban areas, pollutants create more chemically active residues. The same fixture can age at very different speeds depending on where it is installed.

Over time, the weakening of one component reduces clamping force. Reduced clamping force increases movement. Movement increases oxidation. The interaction becomes circular and self-reinforcing.

Why Does My Outdoor Light Flicker Only After Rain?

The fixture looks dry from the outside. The bulb is tight. Yet the flicker shows up almost every time it rains. This moment creates confusion because nothing obvious appears broken.

Moisture does not need to pool visibly to influence performance. Thin films of condensation can form inside enclosures after temperature shifts. These films are enough to change how electricity moves across partially oxidized contacts.

Several small but distinct factors can be at play.

Why does it flicker only when the air feels damp? Because humidity increases surface conductivity across oxidized terminals.

Can a light work fine all summer and start failing in fall? Yes. Cooler nights increase condensation inside enclosed fixtures.

Why does replacing the bulb not fix it? Because the instability originates at the connection, not the filament or LED driver.

Is this more common near sprinklers? Yes. Repeated spray introduces moisture and dissolved minerals that accelerate oxidation.

Why does it stop flickering when the weather dries out? Because moisture temporarily evaporates, reducing surface conductivity until the next damp cycle.

These questions reflect everyday confusion. The behavior feels weather-related, and in many cases, it is. Moisture amplifies the electrical effects of corrosion that were already developing quietly.

Thermal Cycling and Mechanical Fatigue

Summer heat expands metal. Winter cold contracts it. This constant movement affects every terminal screw and connector inside the fixture.

Even when properly tightened, repeated expansion and contraction can slightly reduce clamping force. Once tension decreases, microscopic gaps appear between contact surfaces. Those gaps allow oxygen and moisture to settle more easily.

The mechanical sequence typically unfolds as:

-

Seasonal expansion loosens tension slightly.

-

Micro-gaps trap moisture.

-

Oxidation forms at contact edges.

-

Reduced surface area increases resistance.

In regions with freeze-thaw cycles, moisture trapped in small crevices can freeze and expand. That expansion subtly shifts contact surfaces. When thawed, the connection may no longer sit as tightly as before.

The electrical consequence builds gradually. Slight resistance increases may not trip a breaker, but they contribute to long-term instability.

Environmental Variables and Corrosion Speed

Air quality and exposure patterns strongly influence corrosion rate. A fixture mounted under a covered porch ages differently than one facing open wind and rain.

The table below illustrates how environmental variables interact with connection behavior.

| Environmental Condition | Primary Interaction | Electrical Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Coastal salt exposure | Salt increases moisture conductivity | Faster galvanic reaction between mixed metals |

| High humidity climate | Persistent thin moisture films | Repeated low-level resistance spikes |

| Heavy irrigation spray | Mineral residue buildup | Accelerated oxidation at terminals |

| Urban pollution | Acidic particles settle on surfaces | Coating degradation and metal thinning |

| Large temperature swings | Frequent expansion and contraction | Reduced clamping force over time |

These variables rarely act alone. Their combined effect determines how quickly corrosion shifts from cosmetic to performance-altering.

Understanding this interaction clarifies why some fixtures fail earlier than expected. Broader performance decline patterns over time are explored in this related analysis: Why Outdoor Lights Stop Working Over Time explores the layered mechanical and electrical factors that gradually reduce fixture performance.

Structured Differentiation: How Conditions Change the Pattern

The same fixture behaves very differently depending on where it is installed. A wall light near the ocean ages in a way that looks nothing like one mounted in a dry inland climate. The metal does not corrode randomly; it reacts to its surroundings.

Coastal installations

-

Salt increases conductivity within moisture films.

-

Galvanic imbalance accelerates between mixed metals.

-

Pitting appears earlier and spreads faster.

In these areas, even well-sealed fixtures show corrosion sooner because salt lowers the threshold for electrochemical reaction.

Dry desert climates

-

Overall oxidation progresses more slowly.

-

Sudden failures often follow rare heavy storms.

-

Dust accumulation can trap brief moisture episodes.

Here, corrosion tends to be episodic rather than constant. Long dry periods delay progression, but isolated moisture events can trigger rapid localized damage.

Cold northern regions

-

Freeze-thaw cycles stress mechanical tension.

-

Condensation increases during seasonal transitions.

-

Micro-movement at terminals becomes more common.

In these climates, mechanical fatigue compounds chemical change. Corrosion progresses not only because of moisture, but because expansion and contraction alter clamping force.

Urban residential areas

-

Airborne pollutants thin protective coatings.

-

Acidic residues settle on exposed metal.

-

Corrosion patterns appear uneven across components.

Urban exposure often produces irregular degradation, where one screw deteriorates faster than others due to pollutant concentration.

These distinctions show that corrosion does not follow a single timeline. Material pairing, humidity patterns, temperature swings, and environmental chemistry all interact to determine speed and severity.

When Corrosion Becomes a Structural Electrical Problem

At some point, the issue stops being about surface discoloration and becomes about structural reliability. A screw that once held firm may begin to strip. A terminal that once felt solid may now shift slightly under pressure.

Structural transition typically includes:

-

Noticeable reduction in thread strength.

-

Visible metal thinning or flaking.

-

Darkened insulation near contact points.

-

Increasing frequency of flicker or outage.

When clamping force declines, electrical resistance becomes less predictable. The connection no longer provides stable surface contact. This shift marks the boundary between cosmetic degradation and functional compromise.

Protective Coatings and Their Limitations

Many fixtures rely on plated screws and corrosion-resistant finishes. These coatings delay oxidation but do not prevent it indefinitely. Once the outer layer wears through, exposed metal reacts quickly under repeated moisture exposure.

Common limitations include:

-

Scratches that expose base metal.

-

UV-hardened gaskets that no longer seal tightly.

-

Condensation forming inside otherwise “weather-rated” housings.

-

Coatings that thin unevenly over time.

Protective layers extend lifespan, but they cannot compensate for persistent environmental stress. Once compromised, corrosion accelerates beneath the surface.

Connection Design and Preventative Stability

Long-term stability depends on more than surface protection. It depends on mechanical tension and environmental control working together.

Effective stabilization strategies often involve:

-

Matching compatible metals to reduce galvanic reaction.

-

Maintaining firm mechanical clamping force.

-

Ensuring seals compress evenly without gaps.

-

Allowing controlled drainage or ventilation to limit trapped condensation.

When both contact pressure and moisture exposure are managed, corrosion progression slows significantly. If only one factor is addressed, recurrence remains likely.

Progressive Electrical Instability and System-Level Impact

As corrosion deepens, the effect spreads beyond a single screw. Resistance at one connection can influence voltage stability across the circuit.

Observable system-level patterns may include:

-

Flickering across multiple fixtures.

-

Increased transformer strain in low-voltage systems.

-

Intermittent outages during damp weather.

-

Breaker trips tied to environmental shifts.

This broader instability is rarely caused by simultaneous product failure. It reflects cumulative degradation at shared connection points.

Recognizing the Point of No Return

There is a stage where surface correction no longer restores reliability. Threads lose grip. Terminals deform. Insulation shows heat-related damage.

Indicators that replacement may be more appropriate include:

-

Crumbling screw heads.

-

Persistent arcing marks.

-

Repeated seasonal instability despite prior correction.

-

Visible metal geometry changes at contact surfaces.

Once structural integrity declines beyond a threshold, ongoing minor adjustments may delay but not prevent recurrence. At that point, the connection itself has changed in ways that cannot be fully reversed.

For industry-backed standards on environmental protection and enclosure performance, see National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA).